Some years ago this column started its annual analysis called “The Great Space Race”. The idea was that while the original “Moon race” ended in 1969 when the USA beat the Soviet Union onto the lunar surface with its Apollo 11 human landing, a new one has started – and this time with more than two runners. This time around there is more than a single target with both the Moon and eventually Mars as planned human exploration destinations. Thus we have split the analysis into two – one for the Moon and one for Mars. In the analysis we judge each space programme on the basis of technological ability, financial and other resources, national will and, most importantly, project progress. In conclusion we assess each nation’s chances in the way that a notional bookmaker would: in the form of odds.

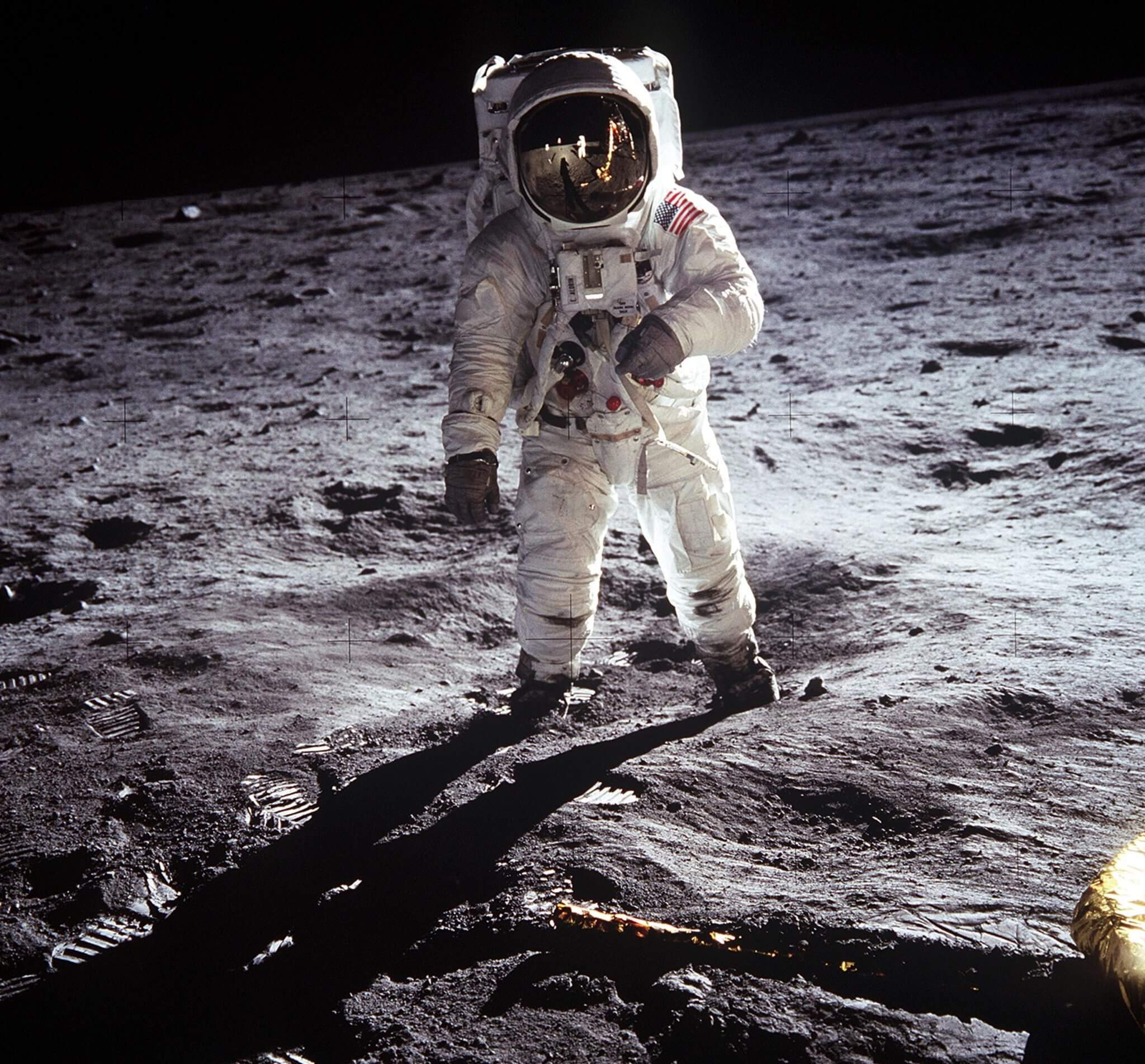

Buzz Aldrin is photographed on Moon by Neil Armstrong (seen in Aldrin’s helmet visor) during Apollo 11’s lunar walk. Courtesy: NASA

While the original race was the USA versus the Soviet Union, nowadays the two man protagonists are the USA and China, with Russia doing its best to catch the main pair. That said, some others also have human spaceflights aspirations, most notably India whose programme which unlike its unmanned efforts, arguably has no justification except for national pride. This year, while there have been some delays, there has been little movement in the odds of the main participants.

USA: Lunar return odds: Evens; Mars race odds: 1-2 (2 to 1 on)

With the departure of the Trump administration, the previous 2024 human lunar landing deadline has been put aside. NASA however, has made some progress. Its admittedly very late SLS human-rated heavy lift launch vehicle (HLV) is just about ready for the Artemis I uncrewed Orion spacecraft test flight around the Moon on the Artemis I mission. This is due to be launched by the end of 2021 – although March 2022 is now thought more likely. This is to be followed by the Artemis II crewed test flight in 2023. An attempt to land on the Moon will be made by Artemis III in 2024.

Hard on its heals is the launch of the SpaceX HLV, the Starship/Super Heavy combination which may even beat the SLS to orbit. This development is important as there was a significant announcement during 2021 in which NASA formally selected SpaceX to create a new version of its Starship to be its Human Landing System (HLS). This was to the chagrin of Blue Origin whose team, at one stage, looked certain to be one of the two finalists in the HLS competition (the other contender was the Dynetics team).

In the end, given its limited funding, NASA found itself choosing just one finalist – SpaceX, reasoning that its programme was the most advanced. Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos has since countered with a US$2 billion move to demonstrate his spacecraft in orbit in order to stay in NASA’s Artemis programme. Of course, there are still things to be perfected for both SpaceX and Blue Origin – most notably cryogenic storage and refuelling technologies – as both teams have chosen liquid methane/Liquid oxygen (LOx) as its chosen propellant combination.

While the official Artemis III first human lunar return landing date is still 2024, it is now regarded as not likely to be achieved (by the way NASA plans to have both men and women walking on the Moon). Thus the landing is now more likely to be achieved the following year.

NASA still has Mars as its main target. Whether this uses Elon Musk’s plan, or just uses his Starship vehicles as the Earth/Mars injection stages (along with their quick refuelling), this technology puts USA way ahead of its competitors. Thus USA remains the 1-2 favourite in the Mars race.

Update on 16 August 2021: It has been noted that while the lunar surface return Artemis III mission is currently due to take place in late 2024, the space suits needed for Moonwalk, and which, unlike the current NASA ones, have moving legs, will not be ready until 2025 at the earliest.

Update on 17 August 2021: Blue Origin, having offered to test fly its lander free of charge, has now decided to sue NASA over its HLS selection of SpaceX.

China: Lunar return odds: 2-1; Mars race odds: 3-1

China is already developing its own HLV, the Long March 9 (CZ-9), albeit that there appears to have been a last minute change of design concept from an SLS style core plus boosters to a SpaceX superbooster style single core. It is also certain to develop its own human lunar landing system.

Update on 9 August: It has now been confirmed that China has formally started a lunar landing craft programme.

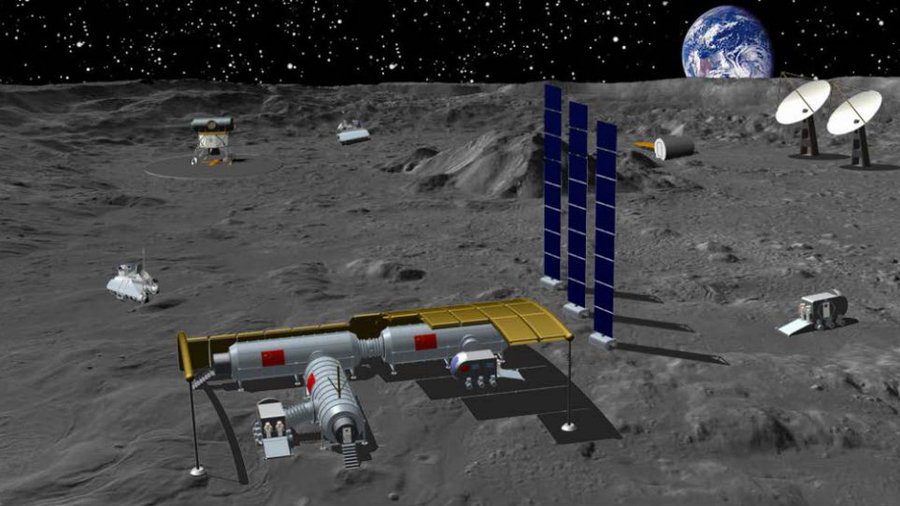

Nevertheless, it has formed an alliance with Russia to build a lunar base dubbed the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). This will involve several unmanned surveying and landing missions to prospect for a suitable base site. But China is not in a rush to get to the Moon. It formally announced that it wants to concentrate more on its Tiangong large LEO space station, which had its Tianhe core section launched in 2021. Thus any Chinese human “Taikonaut” lunar landing mission is unlikely to take place before the 2030s. Nevertheless, should the USA hare falter, the slow but steady tortoise that is the Chinese manned space programme will unrelentingly carry on to achieve this feat. Its highly successful unmanned Chang’e 5 lunar sample return mission programme is a testament to that. The Chang’e 6 sampling mission to the lunar south pole is expected in 2023. China could conceivably launch a lunar landing mission before that. Aviation Week and Space Technology reports that China may be working on a smaller HLV carrying 25 metric tons to TLI, leading to speculation that such a rocket might be able to achieve an Apollo-class landing before the 2020s are out.

The conclusion remains the same as we made last year: while the Chinese tortoise might not beat the US hare, it has solid plans to stay.

Whether China then plans to move towards Mars remains to be seen. It must be tempting to beat the USA in that race, if only to demonstrate technical, political and cultural superiority. With the Long March 9 and the ability to assemble modules for a mission starting in LEO, such a mission is entirely conceivable.

So while China has now lost its favourite status in the Moon return race, its odds having moved out from evens to 2-1 last year, this was more in response to the USA speeding up its efforts than to any change to China’s plan. It remains second favourite for Mars.

Russia: Lunar return odds: 10-1; Mars race odds: 8-1

While Russia continuously moots the development of a new the 100 metric-ton-to-LEO capable Yenisei HLV design (this will be its third after the failed N-1 Moon rocket and the discarded Energia), funding issues have resulted in insignificant progress. A sign of Roscosmos’ own reduced scope was the fact that it had joined up with China’s Moon base programme. Nevertheless, Russia has its Angara rocket, which, while not a proper HLV is still useful to this joint programme in transferring cargo to the Moon. It could theoretically be used to mount a lunar landing mission if used via an Earth Orbit rendezvous technique to join up an trans lunar injection (TLI) stage with a lander/human carrying spacecraft. As it is, the Federatsiya, a planned successor to the Soyuz human carrying spacecraft, is being developed, but this will not fly until late 2022. Regardless, Russia does not have an lunar landing craft yet (unless one is being developed in secret).

Nevertheless, Russia remains a dark horse with respect to the race to Mars and may still have aspirations to mount a mission there.

India: Lunar return odds: 80-1; Mars race odds: 500-1

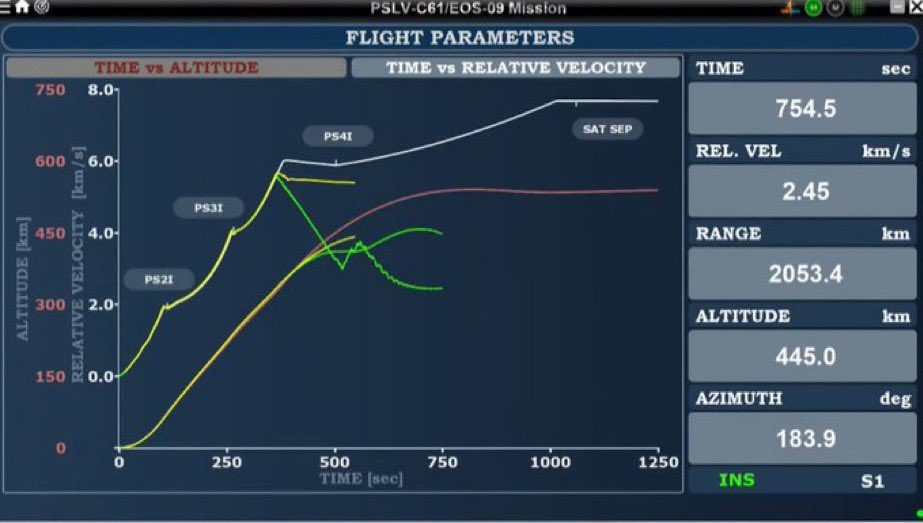

Just like other nations, national pride, and the hunt for international kudos have led India into the world of human spaceflight. However, it is struggling with the human life support needs of this mission not least because of the Covid-19 pandemic which has significantly delayed the programme. The first GLSV Mk III launch of an unmanned version of its crew carrying Gaganyaan spacecraft has now been delayed until 2022. And so its human “Gaganauts” will probably have to wait until 2023 at the earliest to get their flights.

While India has shown it can launch both lunar landing and Mars orbiting unmanned spacecraft, it lacks a rocket large enough to carry astronauts to the Moon – even if an Earth rendezvous technique might reduce the launch payload requirements somewhat. Of course, India will also need a landing craft albeit that this might be achieved by scaling up its unmanned Chandrayann 2 Vikram lander.

While India has shown it can launch both lunar landing and Mars orbiting unmanned spacecraft, it lacks a rocket large enough to carry astronauts to the Moon – even if an Earth rendezvous technique might reduce the launch payload requirements somewhat. Of course, India will also need a landing craft albeit that this might be achieved by scaling up its unmanned Chandrayann 2 Vikram lander.

Thus, India remains very much, the outsider in the lunar and Mars races. But at least it is in these races.

The other contenders: 1000-1 for both races

As for the others, the status has not changed. The European Space Agency (ESA), and Japan’s space agency JAXA, are content to be subordinate to NASA’s efforts in the Artemis programme. They really do not have the funding to do otherwise. The United Kingdom is in the same boat and will hope that its astronauts will get to the Moon on the back of NASA’s Artemis mission – probably after the Lunar Gateway Moon-orbiting space station is constructed.

Final Comment: The Moon is where the money is…but let us get Mars out of our system

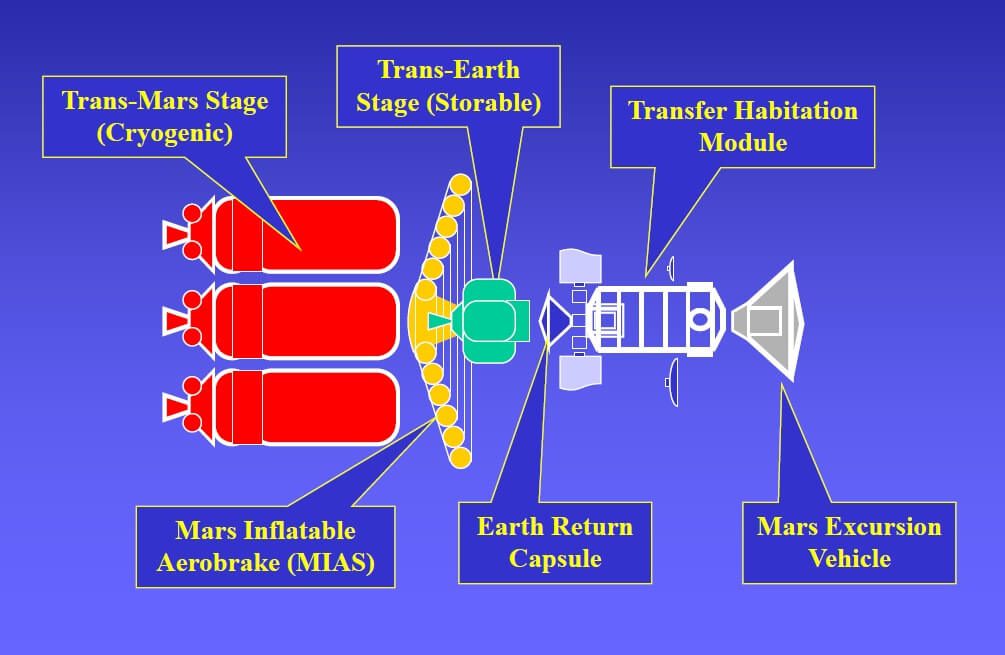

Bob Parkinson’s plan: elements needed for basic human landing mission to Mars. Courtesy: Bob Parkinson

Many now realise that the Moon offers significant commercial and scientific opportunities such as space mining (the Moon’s significant gravity makes it much easier to mine than asteroids), space hotels (affluent would-be space tourists might go on a two week lunar holiday but not on a two year trip to Mars, let alone stay there as colonists), and astronomy (visual and radio astronomy would be much less affected by electromagnetic or light pollution with observatories on the far side of the Moon.) Hence, why US enterprises (both public and private) such as SpaceX and Blue Origin are so interested in going to the Moon, as are the likes of China and Russia.

As it is NASA, wants to use the Moon as a test bed for some of its Mars exploration technologies, albeit not wanting to get “bogged down” there as it keeps its eyes on the prize: Mars. Even if it is just a one off human landing mission to “get it out of our system”. Whether that is via the use of Elon Musk’s Starship infrastructure as part of his Mars “colonisation” plan, or using elements of it as part of a NASA architecture which is likely to be similar to that proposed by UK British Interplanetary Society expert Dr Bob Parkinson remains to be seen. Either way, USA is still ahead despite NASA’s inconsistent funding.