Every August – the silly season when hard news is hard to come by – this column does its bit to help out with an analysis of the runners and riders in the “Great Space Race”. We rate space nations’ space programmes in the form of bookmaker’s odds, according to which has the highest chance of achieving a human return to the Moon, and to be the first to put humans onto Mars. In the analysis we judge each space programme based on technological ability, financial and other resources, national will and, most importantly, project progress.

Over the years there have been some entrants who were strong, for a time, but which have fallen away. One amusing, and surprising, example was the Isle of Man which propelled this column into the national news when we rated it fifth. Others which fell away, have since returned: India, with a solid human spaceflight programme now in place – even if it has no real justification except for national pride – is a case in point.

Some, like Russia, have been contenders in the (distant) past, but now lack financial resources and have been reduced to “outsider” status.

Of the two main contenders, the USA and China, it all depends on the decisions made: ranging from the dithering of past administrations to (currently) being overly optimistic about the readiness of hardware and technology.

USA Lunar return odds: Lengthened to 5-4 (no longer favourite on its own); USA Mars race odds: 1-2 (odds on favourite)

While former US President Donald Trump has many detractors, it must be said that he was not wrong about everything. One of the things he got right was to give NASA a proper set of objectives after it drifted so long under the previous Obama administration. Unfortunately, Obama’s Vice President Joe Biden, who was then in charge of the drifting space programme, is now the US President. So, this column has been on alert for signs of a return to the drifting malaise. There were initially some ominous signs with the target date of 2024 for a human return to the Moon being put aside.

Nevertheless, there are signs of progress in some areas. After years of delay, the SLS human-rated heavy-lift launch vehicle (HLV) passed its fuelling acceptance tests and is now expected to launch in October after its initial attempt was scrubbed on 29 August due to engine temperature sensor issue and a subsequent attempt on 3 September was similarly stymied by a hydrogen leak.

While there is no crew, the flight is high risk. Although it uses a great deal of past space technology – most notably the repurposed RS-25 shuttle main engines – it is still a new rocket. And new rockets on their maiden flights are prone to failure. According to the Seradata database, new rockets flown since 2000 have a failure rate of 43 per cent on their first flights.

The key piece in being able to fly humans to and from the Moon – the Orion spacecraft – will also be on Artemis I’s 42-day lunar orbit testing mission launch. Thus, if both are lost this could set the Artemis lunar return programme back by years.

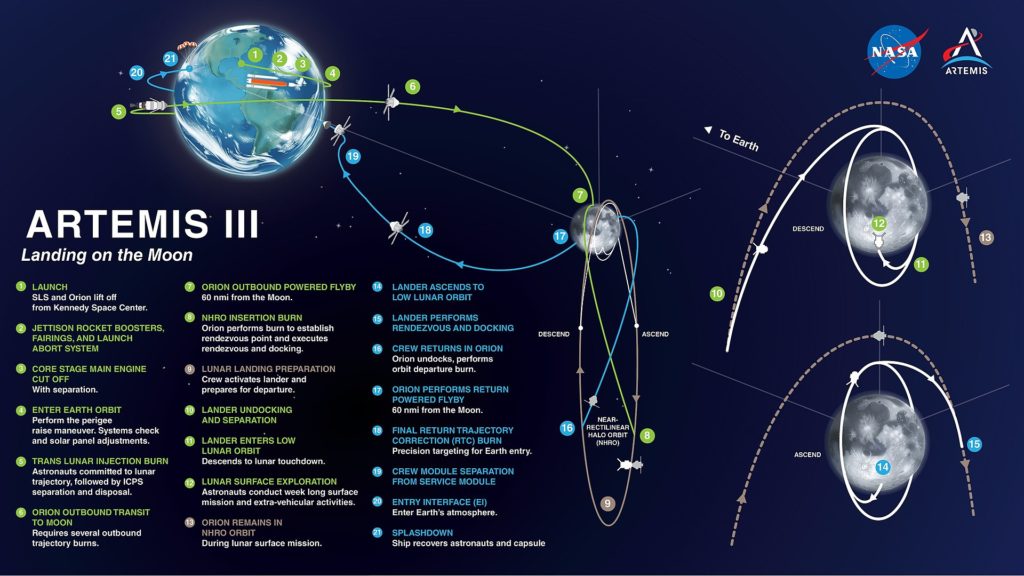

Even if the launch, mission and the subsequent Artemis II, a human-carrying non-landing lunar mission, are all successful, the question remains about how exactly NASA plans to land its astronauts on the surface of the Moon? And by when?

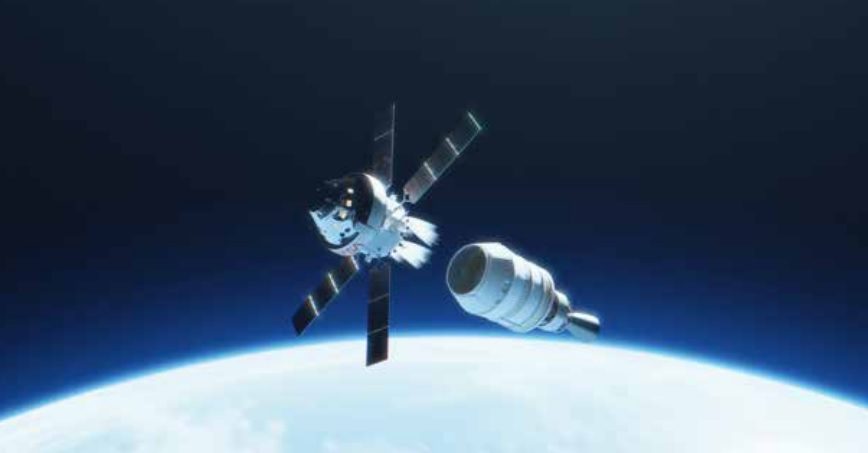

Artist’s impression of Orion separating from its ICPS after being Trans Lunar Injected. Courtesy: NASA

Officially the Artemis III human landing attempt will take place in 2025, with two out of the four crew landing for a geology/science surface mission near to the lunar South pole. For the moment, however, NASA is without a ready-to-go lander. Rather than building a simple interim craft as a first lander – a kind of “son of the Apollo LEM” using storable propellants – NASA has opted to take a gamble and use the untried SpaceX design for an exceptionally large landing craft as its Human Landing System (HLS). This will require the storage of cryogenic liquid natural gas (mainly liquid methane) and LOx (liquid oxygen) and the in-space transfer of these propellants. While this technology may be the future of space travel, its readiness level is simply not yet mature enough to allow such a landing within the next five years. Even NASA has noted that a lander might not be ready in time and has a back-up plan to make the Artemis III landing mission another human lunar fly-by mission.

NASA also wants a second lander design for its later operations to, and from, the Lunar Gateway space station. Thus, the likes of Blue Origin whose team, at one stage, looked certain to be one of the two finalists in the HLS competition (Dynetics was the other contender) might get back into lunar operations – but this would be a follow-on lunar lander which, again, would employ cryogenic propellants.

The Artemis I mission is due to be launched by the end of September, followed by the Artemis II crewed test flight in 2023. Thus, we expect an attempt to land on the Moon by Artemis III in 2028 at the earliest – whatever NASA may say to the contrary, and we have lengthened the USA’s odds from evens (1-1) to 5-4. This means that China now joins the USA as joint favourites in the race for a human return to the Moon.

For Mars, the USA is the only game in town. A basic launch using quick-launch Starship/Super Heavy hardware could easily send a large mission, with a storable propellant return stage, to Mars by the mid-2030s. However, its originator, Elon Musk, will be keener to stick to his own plan for in-situ propellant generation on the surface of Mars – again a technology that has yet to be proven.

Bob Parkinson’s plan: elements needed for basic human landing mission to Mars. Courtesy: Bob Parkinson/British Interplanetary Society

NASA still has Mars as its main target. Whether it uses Elon Musk’s plan, or just his Starship vehicles as trans-Mars stages for an initial NASA designed mission, SpaceX’s reusable heavy-lift technology puts the USA ahead of its competitors. Consequently, it remains the 1-2 favourite in the Mars race.

China: Lunar return odds: now becomes 5-4 joint favourite; Mars race odds: 3-1

China is already developing its own HLV, the Long March 9 (CZ-9), but it still seems subject to last-minute design changes. An example is moving from an SLS-style core, plus boosters, to a SpaceX-style re-useable super booster.

The latest rendition has a 16-engine first stage powered by methane/LOx engines. It has four engines on the LOx/Hydrogen second stage plus another LOx/Hydrogen engine for the third stage. However, the first stage and second stage core diameter has been increased to 11 metres, while the third stage diameter is 7.5 metres. The total length has been increased to 111 metres, with a mass of 4,122 metric tons, and all external boosters have been removed.

The payload capacity to low Earth orbit (LEO) has increased from 140 to 150 metric tons. The trans-lunar injection (TLI) payload capacity has also increased to 50 tons. While China still has some way to go before putting the Long March 9 into production, it may be ready before the decade is out.

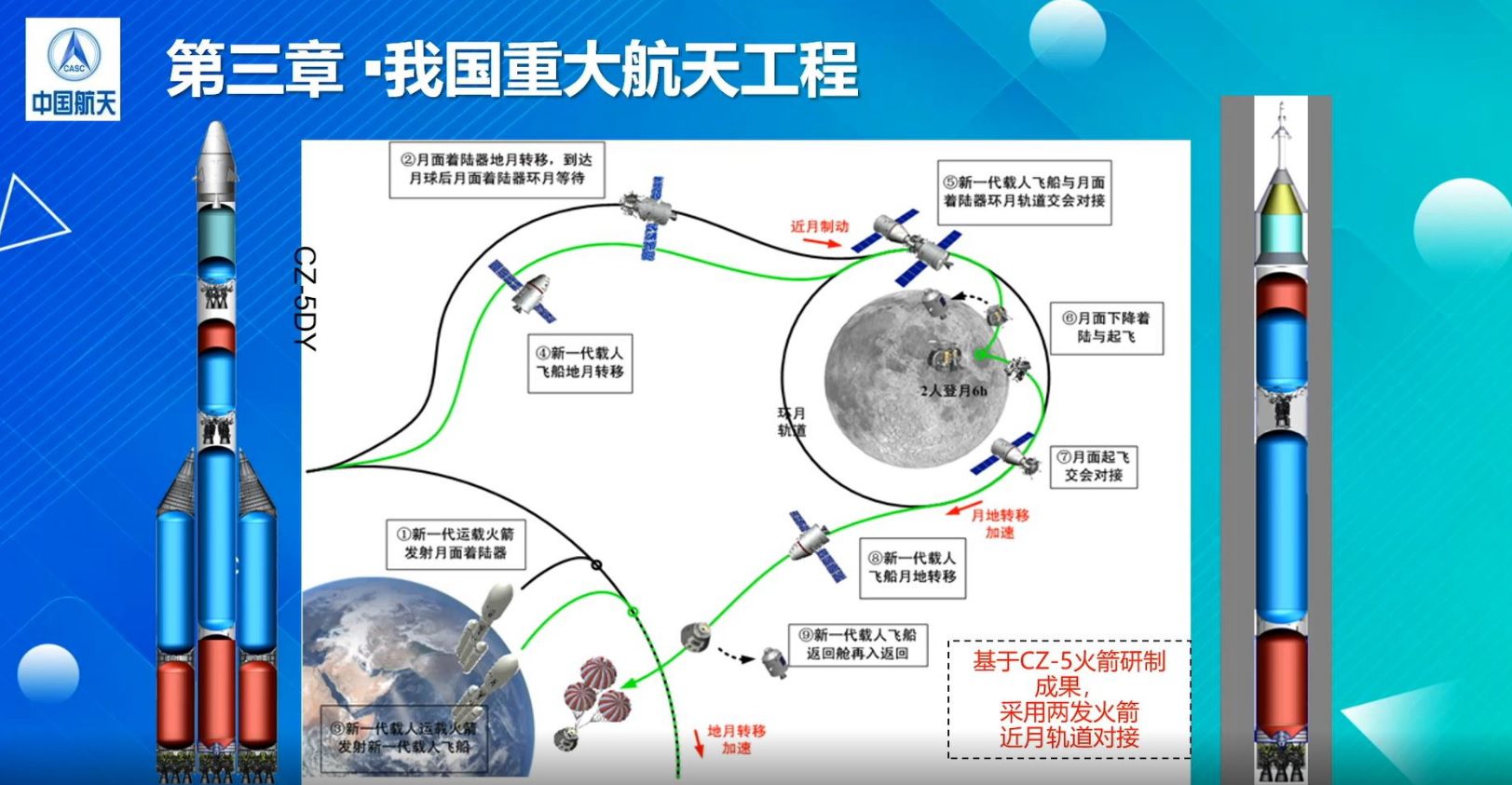

Last year it was confirmed that China had started a lunar landing craft programme. It will be a two-launch mission architecture in which a crew transport vehicle will rendezvous and dock with a pre-launched lander in a low lunar orbit, much like Apollo’s mission plan. After the landing, the ascent stage will rendezvous with the main lunar transport in low Lunar orbit, ready for the return home.

Unlike NASA’s service-module-limited Orion, the Chinese have designed their crew transportation equivalent of Orion with enough propulsion to allow operations in low lunar orbit. Any lunar lander used by the USA will either need extra fuel or an additional transfer stage to and from a low lunar orbit from the Gateway’s near rectilinear Halo high orbit, even with its nearer perilune pass.

The eventual plan for China is to build a lunar base – most likely via its alliance with Russia. The base is dubbed the “International Lunar Research Station” (ILRS). The next unmanned Chinese lunar flight is the Chang’e 6 sampling mission to the lunar south pole which is expected in 2023.

It has been reported that China could launch a lunar landing mission well before its Long March 9 rocket is ready. China is developing a smaller Long March-5DY HLV able to put 70 metric tons into LEO and 25 metric tons into TLI. This is a derivative of the Long March 5, which uses its core stage as the basis of two LOx/Kerosene boosters and a LOx/Kerosene burning extra stage beneath a LOx/Hydrogen upper stage. In other words, the Long March-5DY rocket has a main stage plus two boosters, each with seven YF-100K engines. The second stage has two YF-100M engines and the final stage has three YF-75E engines. This could give China the ability to launch an, albeit basic, Apollo-class lunar landing mission within five years.

NASA briefly considered using Sidemount, the close Shuttle-derivative that had similar performance, for a simplified two-launch human lunar landing.

Having been second favourite last year, China now becomes joint 6-4 favourite with the USA. This is the result of poor decision making in the US camp – not least over the choice of initial landing craft – and it has given China a real chance of beating the USA back to the Moon, especially if it enacts its Long March 5DY-based interim plan.

Although China has not disclosed official plans for going to Mars – it is evidently thinking about it. Wu Yanhua, deputy director of the China National Space Agency (CNSA), said the main purpose of the Long March 9 Super-Heavy lifter is for any “crewed lunar landing or crewed Mars landing missions”. Officially China refuses to be part of a race to the Moon or Mars, but getting its astronauts (taikonauts) to Mars first would be the ultimate way of peacefully showing China’s prowess as a major power. We suspect that China is secretly working on a plan but will not formally announce this until after it has achieved a human lunar landing.

Russia Lunar return odds: lengthened from 10-1 to 20-1; Mars race odds lengthened from 8-1 to 10-1

While Russia continuously moots the Yenisei HLV rocket, it has made little apparent progress to date. In a 2019 official proclamation, the then head of Roscosmos, Dmitry Rogozin, announced that Yenisei, which uses a cluster of LOx/Kerosene burning boosters around a central core, would go ahead.

Officially the first launch of the new 100-metric-ton class design will take place in 2028 from the Vostochny rocket launch site in far east Russia, but little news has been released and it is not even certain that the design has been finalised. There has also been talk of a “Don” derivative with an extra stage being mentioned.

Beset with funding issues, corruption and mismanagement, the Russian space programme is even struggling to produce the Federatsiya, a planned successor to the Soyuz human-carrying spacecraft. It is a sign of Roscosmos’s reduced scope that it joined China’s Moon base programme. Russia still does not have a lunar landing craft, although one can assume that it is having one developed in secret. Unlike its original single-cosmonaut LK design, which never got its chance to land (the N-1 launch failures and its subsequent cancellation saw to that), the new design will carry at least two humans.

The Russian LK-3 lunar lander (with a drawing of the N-1 rocket behind it) was only designed to carry one cosmonaut. Courtesy: Wikipedia

Mars remains on Russia’s wish list, and no doubt plans for a Russian human landing on the planet – as yet underfunded ones – are continually being modified and updated. But an expensive war in Ukraine precludes that for decades. So its odds for that and for its lunar landing have been lengthened.

India: Lunar return odds: 80-1; Mars race odds: 500-1

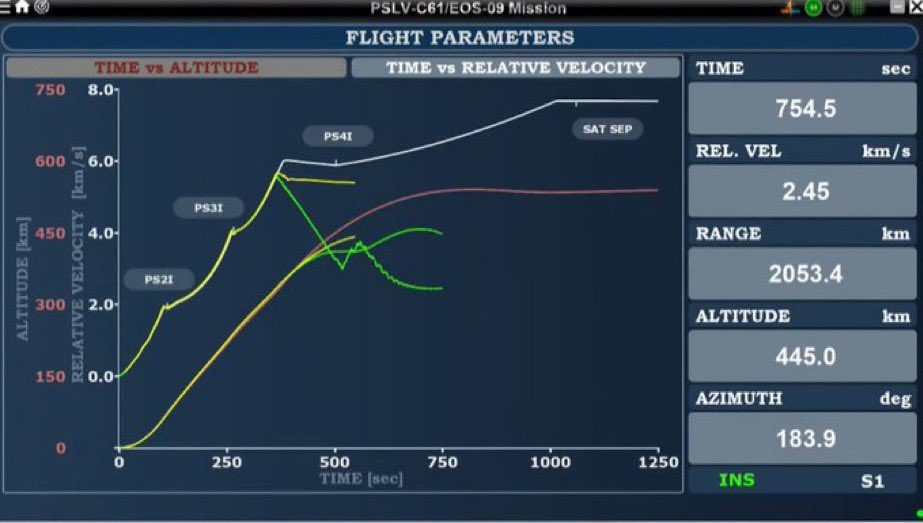

In a bid to compete with its regional rival China, India has made a move into the world of human spaceflight. While the Covid-19 pandemic significantly delayed India’s human spaceflight programme, the GLSV Mk III launch of an unmanned flight carrying Gaganyaan spacecraft is expected to be flown later this year. Assuming it is successful, there will be a human spaceflight by male and female “Gaganauts” in 2023.

Whether the spacecraft can be turned into a craft capable of return from the Moon remains to be seen. Currently India does not have a large enough rocket that would make this flight a realistic possibility. Similarly, it has no lunar lander for humans, although it has shown prowess in landing the unmanned Chandrayann 2 Vikram. So, while India could conceivably achieve a human lunar landing one day, this will not happen until the 2030s at the earliest. Likewise, Mars is probably out of the question for now, and so India remains very much an outsider.

The other contenders: 1000-1 for both races

The European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan’s space agency, JAXA, are content to be subordinate to NASA’s efforts in the Artemis programme. They lack the funding to do otherwise. The UK is in the same boat with hopes for its astronauts to reach the Moon resting entirely on NASA’s Artemis mission. Nevertheless, should Reaction Engines’ single-stage-to-orbit spaceplane, Skylon, ever fly successfully and offer regular access to space, then lunar and Martian exploration could return to the table.

Final Comment: It did not have to be this way…but our money is on China

The Moon offers significant commercial and scientific opportunities ranging from astronomy and space tourism to raw materials via mining. So it is near certain that humans will walk again on the Moon’s surface within the next 15 years – and probably before the end of the decade.

As to which nationality will make those coveted strides: since the USA has elected to go for a large lunar lander using SpaceX’s design, there will be an inevitable delay. Meanwhile, China is showing signs of speeding up, by considering an initial smaller lunar exploration mission architecture for its early flights, and may pip the USA to the post. Our estimate is that the China Manned Space Flight Office may be able to attempt a lunar landing by 2028 or 2029.

Mars is a longer shot for all. While colonisation of the planet seems unlikely, a human mission to Mars is entirely feasible – especially due to Elon Musk and his Starship/Super Heavy combination. But a word of warning: it seems that China is about to copy Musk’s heavy-lift design for its longer-range goals, which include Mars. If China does beat the USA back to the Moon, a true race to Mars will be on.