“Stronger than steel”

“Stiffer than diamonds”

“Capable of sitting on the surface on the sun”

No, it’s not superman: It’s graphene.

These were just some of the superlatives claimed to describe the “frontier material” in a workshop held during the UK Space Conference. It seemed an apt topic given that the host city, Manchester, happens to be the place where graphene was created for the first time. Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov first isolated graphene from graphite at the University of Manchester in 2004. They won the Nobel prize for physics for their work in 2010.

What is graphene?

At its core, graphene is a single crystal layer of carbon that is one atom thick. Multiple sheets of these can be used to make graphene film. This new material is frequently touted as the strongest man-made material on Earth. Graphene is also exceptionally light, flexible and conductive (it even outperforms diamond in thermal conductivity). It is also the thinnest imaginable material – one million times thinner than a strand of human hair.

Graphene film is frequently touted as the strongest man-made material on Earth and could have applications for space. Courtesy: Farah Ghouri using ChatGPT

From rocket fuel to satellite coatings: space applications multiply

As the Editor of a journal dedicated to graphene, Adrian Nixon has been keeping an eye on the development of the material since its inception. He presented some of the ways graphene can be used in engineering, including in science and technology at the UK Space Conference. Between 2020 to 2024, US$1.3 billion was invested in graphene applications including in computer hardware (US$272m), batteries (US$249m), and supercapacitors (US$245m). There have also been developments in the applications of graphene for space.

In the US, Purdue University developed a super lightweight and reusable graphene foam structure, that can be loaded with solid rocket propellant, in 2019. They reported enhanced burn rates nine times that of normal solid fuel, according to Nixon. The material can also be used in aerospace structures.

UK rocket manufacturer Orbex has built a launch vehicle with a graphene enhanced carbon fibre body. Orbex Prime is a two-stage rocket designed to carry up to 200kg of payload, set to launch from SaxaVord, Scotland in early 2026.

The China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology (CALT) revealed that it has designed a graphene composite film suitable for use in light-propelled spacecraft: graphene sails. The European Space Agency (ESA) also successfully tested a one atom thin graphene solar sail at the ZARM drop tower in Bremen, Germany.

Graphene’s applications could even extend to Mars. The formidable distance to the red planet means transporting materials and resources is a time consuming and expensive method of building infrastructure there. Utilising the materials already on the planet offers a more attractive route. Dekiln, a startup also based in Manchester, have discovered that graphene can enhance the ability of ordinary starch to bind regolith. The resulting material, dubbed ‘Starcrete’, has a compressive strength of 90 GPa – this is the top end for high performance concrete.

SmartIR Ltd is a startup developing a lightweight graphene-based smart coating for satellites, making it possible to control the thermal emissions of a surface. This means that satellites can be better protected from extreme temperature changes in space. The coatings could also provide camouflage from infra-red detection, a useful trait in a military or defence context.

Crucially, the technology can cut satellite weight by up to 10% and power consumption by up to 40%, claimed Margherita Sepioni, the CEO and co-founder of SmartIR. She added that these figures have been validated by Airbus for weights ranging from 1-1.5 kg. “By saving power consumption, we reduce mass, which cuts costs by 10%,” said Sepioni. The startup claims this would amount to a saving of US$4.2billion focussing just on medium and large class satellites.

Why companies are banking on graphene – only quietly

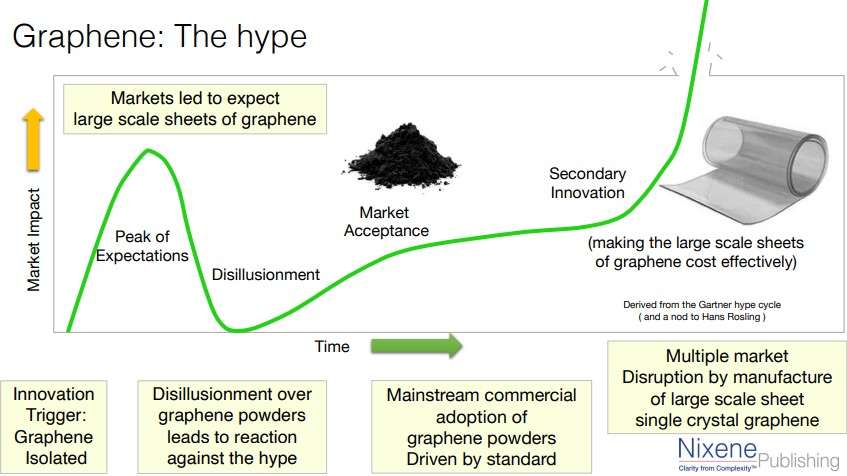

It can take decades for new technologies to fulfil their full economic potential. On the way there, there are many hazards. Excessive hype is one of them. Graphene suffered from this after its initial discovery, over 20 years ago. Industrialising the material proved difficult because it was too expensive to extract in large quantities, and disillusionment set in.

A look at Graphene’s entrance to the marketplace, based on the Gartner hype cycle. Courtesy: Nixene publishing

However, Professor James Baker, CEO of Graphene@Manchester, believes we are at a ‘tipping point’ in the commercialisation of graphene products and applications, with many products now in the market or close to entering. This is partly due to new production methods being applied as well as experimentation with different forms of graphene. Even though graphene is still expensive to develop, production costs have come down significantly relative to where they started.

Graphene is already being used in some everyday items like iphones, tennis rackets and car components. However, Nixon and Sepioni claimed that because the material gives companies a competitive edge, they prefer to keep quiet about it.