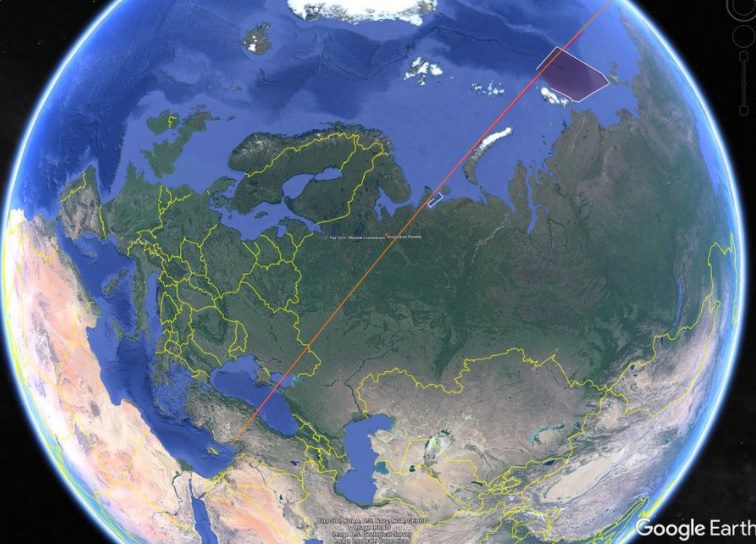

Russia has conducted its fourth ground-based anti-satellite (ASAT) missile test and, in doing so, it threatened the safety of the International Space Station (ISS). A Russian A-235/PL-19 Nudol missile was launched on 15 November from Plesetsk in Northern Russia. Taking off at 0246 GMT, it intercepted a defunct Soviet era satellite about five minutes later. The intercepted satellite, Cosmos 1408, was a Tselina-D class signals intelligence satellite originally launched in 1982, which had been defunct for several decades. It apparently blew up when it was struck, causing a “debris cloud”.

This was later confirmed by NASA as the event had triggered the “safe haven” protocol alarm procedure at 0900 GMT on the ISS. The seven astronauts and cosmonauts aboard were instructed to retreat to their spacecraft (Crew Dragon Endurance and Soyuz MS-19) ready for a possible evacuation should the ISS be struck.

It was the relative proximity of the orbits and the short warning that caused particular concern. While the ISS orbit, at 51.6 degrees inclination, is significantly different from that of Cosmos 1408 at 82 degrees, the latter’s 487 x 462 km orbit is close enough to the ISS’s 424 x 418 km to cause a threat every 93 minutes from crossing debris blasted down from an explosion.

Normally when a debris cloud is detected and there is enough time to rate the threat as serious, an onboard engine burn – by the ISS’s propulsion system or engines of an attached spacecraft – is made to change the ISS’s orbit to allow it to “dodge the debris”. This happened on 10 November, when the ISS raised its orbit by 1.2 km to avoid debris from Feng Yun 1C, a Chinese weather satellite, which was also caused by an ASAT test – a Chinese one.

However, in the more recent case there was not enough time to assess the risk or order an engine firing, and so the “safe haven” protocol was triggered instead. After more than two passages of the ISS past the debris cloud, allowing the risk to be properly analysed, the ISS was reportedly back to regular operations by around 1530 GMT.

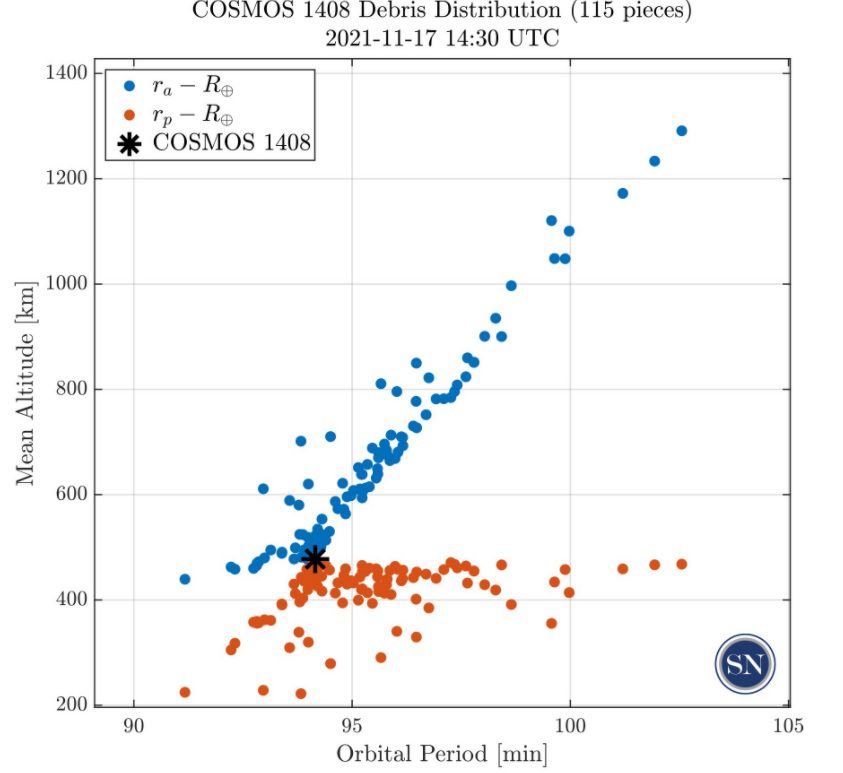

Distribution of debris from ASAT interception strike on Cosmos 1408 shows that some of it has reached considerably higher altitudes. Courtesy: SpaceNav

While anti-satellite Soviet “killer satellites” and air-launched US ASAT missile interceptors were tested in the Cold War era, this ASAT test involved a suspected ground-launched missile strike on a spacecraft. This is the fourth one to have been achieved. On 11 January 2007, a partly moribund Chinese meteorological satellite, Feng Yun 1C, was destroyed by a Chinese ASAT missile at an altitude of 865 km, causing a debris field that prompted international protest. In response, the US Navy mounted its own satellite interception, using a ship-launched Standard Missile-3 to strike USA-193 (NRO L-21) on 21 February 2008. On 27 March 2019, India conducted an ASAT test with a missile that struck Microsat-R at an altitude of circa 300 km.

Update on 16 November 2021: The ASAT test and its resultant debris cloud has resulted in international criticism of Russia. NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said: “I’m outraged by this irresponsible and destabilizing action. With its long and storied history in human spaceflight, it is unthinkable that Russia would endanger not only the American and international partner astronauts on the ISS, but also their own cosmonauts. Their actions are reckless and dangerous, threatening as well the Chinese space station and the taikonauts on board.”

Update on 22 November 2021: While it was initially predicted from past ASAT tests that the debris might exceed 1,500 trackable pieces (note that sub 10 cm pieces cannot be accurately tracked), it now seems this figure will be considerably less – possibly as low as 500. Analysts have suggested that this is because Russia deliberately decided to intercept the satellite from behind, considerably reducing the relative strike velocity and thus the amount of debris produced. While this technique has its merit, it does have a downside: it adds a velocity component to the target spacecraft’s own, which tends to increase the velocity of debris departing the impact. This causes more of the debris to be shot into higher orbits, presenting a hazard to both Earth observation and communications satellites using these higher low Earth orbits. There is also less “cleansing” atmospheric drag there, so any debris has a much slower orbital decay (perhaps decades long) back to re-entry.

Comment by David Todd: While likely to be seething over the event, China’s past form on making its own ASAT test and debris cloud, plus the fact that it does not want to openly criticise its space ally Russia, has meant that it has remained silent. Russia faces a theoretical financial liability given that the space debris from this ASAT test has been tracked. Under Space Liability Convention (1972), a launching state is financially responsible for damage caused by its launched space objects. Russia launched both the direct ascent ASAT missile and the Cosmos 1408 satellite target, so any subsequent damage to other satellites caused by debris is regarded as its fault, hence the potential financial liability.

Post Script: While not yet confirmed as related to the Russian ASAT test, a space debris warning caused NASA to delay a planned 30 November spacewalk EVA (Extravehicular Activity) outside of the ISS by astronauts Thomas Marshburn and Kayla Barron.