Partially reusable launches have been performed many times. The Space Shuttle Orbiter was, in fact, the main stage of a partially reusable rocket system. More recently Elon Musk perfected the concept of fully reusable first stage rockets with his successful Falcon 9/Falcon Heavy series.

However, the holy grail is to create a rocket with completely reusable stages. If this could be achieved it would dramatically reduce the cost of spaceflight, so much so that it would make all other rocket systems redundant. And that is just what Elon Musk and his SpaceX company has done.

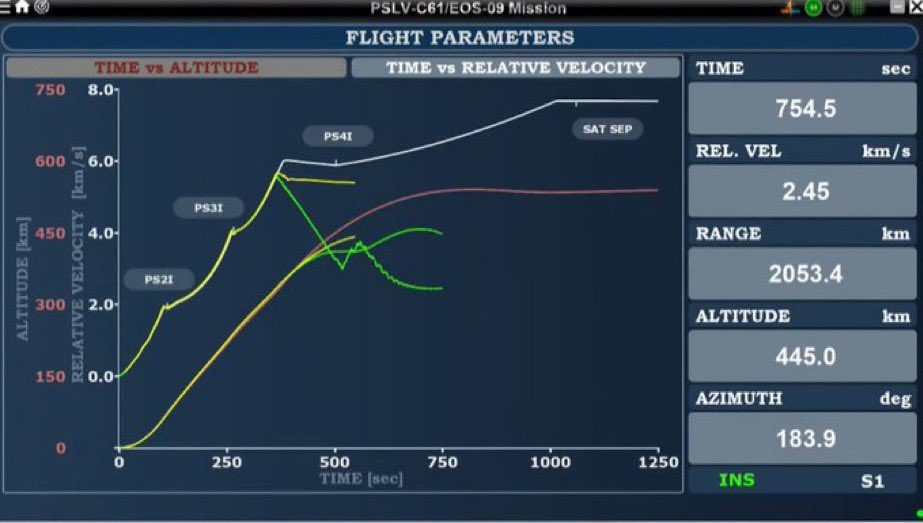

The Super Heavy lost an engine on the fourth flight, but had enough thrust in reserve to make its trajectory. Courtesy: SpaceX/Twitter-X

On its own D-Day of sorts on 6 June, the firm launched its 121 m tall Starship/Super Heavy rocket combination into a near orbital trajectory of its Starship IFT-4 mission. While launching had previously been achieved, this new flight had the aim of testing out its first and second stage re-entry and landing systems. The previous three launches had ended in failure at various points of the flight, the most recent being the re-entry failure of the Starship upper stage.

The launch took off as planned at 1250 GMT from the Starbase launch site near Boca Chica, Texas. But as the rocket blasted itself into the air, it soon became apparent that one of the 33 first stage Raptor engines, used for the initial climb, was out. No matter. The rocket had enough thrust to make this work. Having separated from the Starship hot firing upper stage – the hot staging ring was discarded on this flight for weight reasons – the Super Heavy rocket pitched itself backwards and used the core 13 inner engines to fire itself towards the Atlantic Ocean close to the launch site. The Starship blasted onwards to an apogee of 214 km.

Starship IFT-4’s staging event. Courtesy: SpaceX/Elon Musk

The Starship stage ploughed on, although there was a hiccup in its on-board TV feed for a time. There was another slight problem as, again, two engines failed to reignite. Still no matter though. There was enough thrust to perform its deceleration to make a controlled landing in the sea, seven and a half minutes after launch.

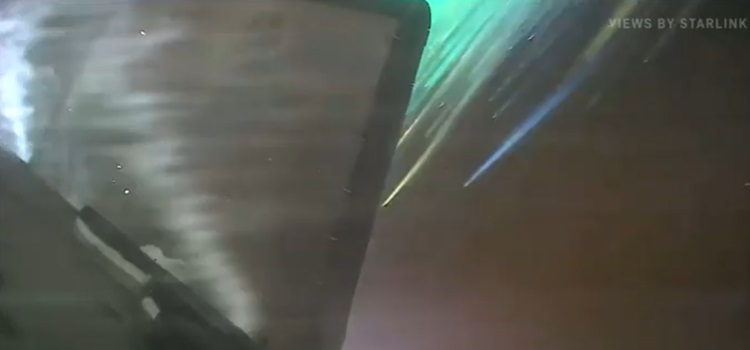

But first there would have to be a fiery re-entry to survive as the craft slowly bled off its velocity. The onboard TV coverage was thankfully restored to view this key part of the mission: to prove that an upper stage can survive re-entry and land in a controlled way – even if it would be a controlled soft-landing to a splashdown in the Indian Ocean an hour after launch this time. The previous mission showed that the stainless steel craft’s thermal protection system, protected by tiles, was just about holding up – until the spacecraft broke apart due to an uncontrolled roll and tumble. The TV views of the re-entry were spectacular, beautiful colours of the fiery plasma on display.

The plasma flow during Starship’s re-entry turned a pretty green on the flap. Courtesy: SpaceX/Twitter-X

However, on examination of the control flap it became obvious that the plasma was starting to burn through its hinge, an area that Elon Musk predicted could be its Achilles’ heel. And yet, despite being nearly hollowed out by thermal melting, the flap just about managed to stay attached to the main body, which was simultaneously losing thermal protection tiles. Impressively, the Starship rocket stage stayed intact long enough for the final gimballing manoeuvre to make the rocket vertical for its powered soft landing into the Ocean. As its charge fell into the drink, 20 km away the capture mechanism, dubbed the ‘chopsticks’, on the pad went through the motions of a simulated grab.

As Musk and his team received congratulations from around the world, the billionaire noted the end result of the mission on his own X/Twitter feed: “Despite loss of many tiles and a damaged flap, Starship made it all the way to a soft landing in the ocean!”

Musk knows that if the final wrinkles of his fully reusable launch system can be ironed out, it will make all other expendable and part reusable launch vehicles obsolete.

Comment by David Todd: While we have sometimes been critical of Musk’s over-optimism – not least over his Human Landing System Starship – we give our total congratulations to him and his team for this world changing achievement.