Every year, Seradata reviews the ‘runners and riders’ in the Great Space Race, or rather the two races: to return humans to the Moon and to land humans on the surface of Mars for the first time.

In this we judge each of the leading contender nations’ space programmes based on their technological capability, financial resources, national commitment and, most importantly, project progress. To quantify each nation’s chances of success, we use traditional betting odds – a precise way to express probability.

Here’s how our odds system works:

When we say a nation has 1-1 odds (called ‘even money’), it means a 50% chance of success. Think of it this way: for every one unit of failure, there’s one unit of success – hence a 50-50 split. The odds format “X-1” shows how many failures are expected for each success. For example, 2-1 odds mean two failures per success, giving a 33% chance while a nation with 4-1 odds would have a 20% chance. For ‘odds-on’ favourites, we use “1-X” odds. For example: 1-2 odds (read as “one-to-two”) means two successes expected per failure, giving a 67% chance. 1-3 odds means three successes per failure, giving a 75% chance.

China has become the odds–on favourite for the Moon – and it is rapidly closing the gap for Mars too.

China (1-2 Moon, 3-1 Mars)

China has a history of human lunar exploration starting with the legend of Wan Hu’s attempt to reach the Moon in a wicker chair with 47 ignited rockets attached to it in 1390. After the resultant explosion, he was never seen again. More recently – and realistically – China’s steady approach for lunar exploration envisages initial human landings before the end of the decade. China has cleverly eschewed using major changes of technology, including a brand–new heavy lift rocket, for its initial crewed lunar flights.

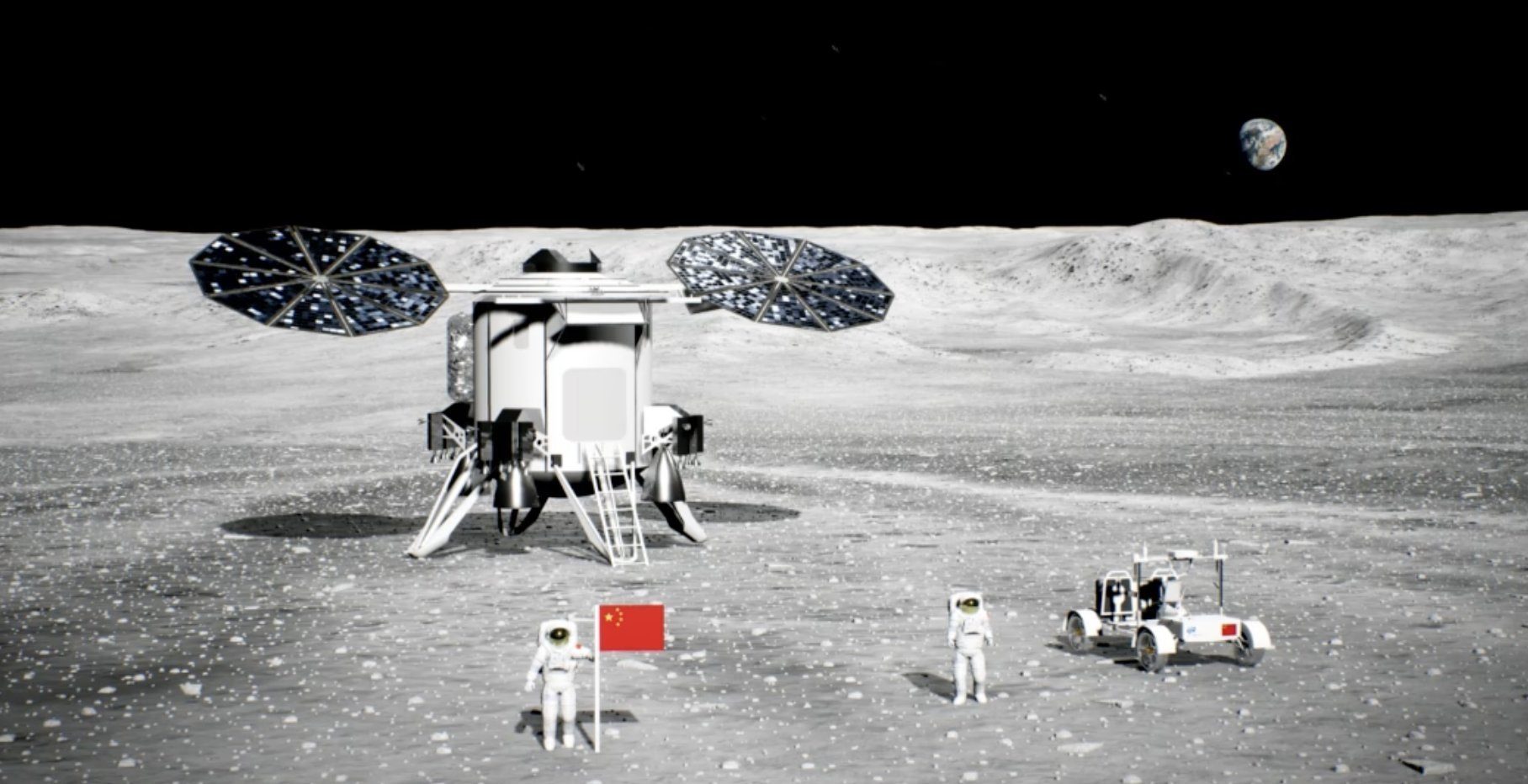

Chinese human-carrying lunar lander concept plus rover. Courtesy: CNSA

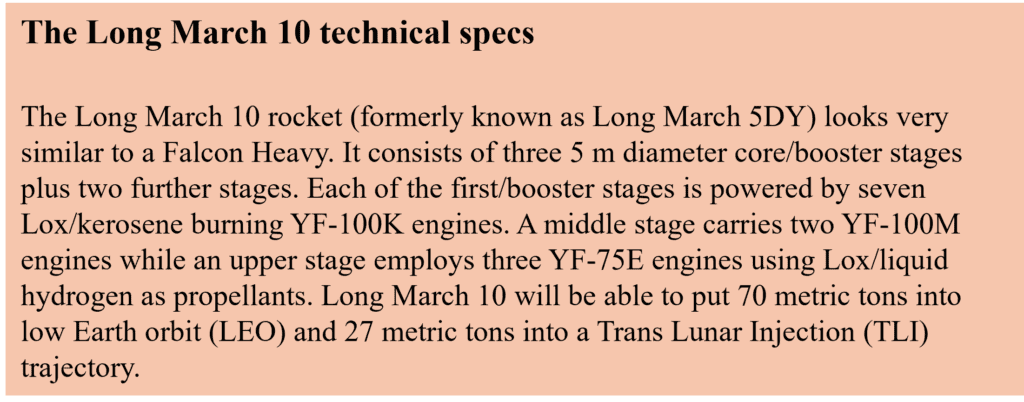

China originally planned to use a new heavy-lift rocket called Long March 9. However, the space nation has since decided to repurpose its Long March 5 hardware to build a smaller rocket for its initial human lunar missions: Long March 10 (CZ-10). This interim rocket will be used in a two-launch strategy for human moon missions: one to deliver the Lanyue landing craft/propellant stage to lunar orbit, and one for Mengzhou, the crew transfer spacecraft. Great strides are being made with the Lanyue’s programme with landing testing already taking place on Earth.

Tethered test of Lanyue lunar lander. Courtesy: CMSA via Weibou

A single core version of the Long March 10 – known as Long March 10A – is set to fly next year. Structural tests of the rocket have, reportedly, been completed. It will be followed by Long March 10 flights. A Chinese human landing attempt is expected between 2028-29.

The crew spacecraft and landing craft/propulsion stage, each weighing 26 metric tons, dock in lunar orbit ahead of a Moon landing attempt. There is no Apollo-style ascent module substage of the lunar lander. Instead, after the landing and excursion activities, the module lifts itself off in one piece using four 7.5 kN engines. It then re–docks with the crew spacecraft so that they can journey back to Earth. As part of the missions, two Apollo-style lunar rovers from CAST and SAST have been ordered for development. These will allow Chinese astronauts (often dubbed ‘Taikonauts’) to make 10 km surface excursions.

Model of the Long March 10 as shown in the National Museum of China. Courtesy: Wikipedia

China does have an unmanned sample return mission to Mars planned for 2031, but it has never officially announced an intention to put its astronauts on the planet. Nevertheless, it has plans for a larger, at least partially reusable rocket: the Long March 9. Its primary use will be the construction of a Sino-led international lunar base, but it would also make in-orbit assembly possible. China’s odds remain stable at 1-2 favourite to land humans back on the Moon. However, its odds of being the first to reach Mars with humans have improved from 5-1 to 3-1 – although this is more to do with the unpredictability in the US space programme than anything that China has done.

The US (6-1 Moon, 1-2 Mars)

Over the last two decades NASA has focussed its attention on returning astronauts to the Moon and even building infrastructure there, as part of a broader plan to eventually land humans on Mars. However, for the Trump administration, the focus is on reaching Mars as soon as possible – without lunar bases slowing them down.

The Starship/SuperHeavy heavy lift launch programme has been delayed after a series of launch failures. However, its latest test was a resounding success and went a long way to proving the full reusability concept. Nevertheless, the testing programme for Starship-derived Human Landing System (HLS) and its key cryogenic transfer and storage technologies, has been delayed. The Lunar Gateway orbiting space station is likely to be cancelled. There has also been dismay and confusion among NASA employees and scientists after funding and personnel cuts (nearly 4,000 personnel – 21% of the NASA workforce – have accepted voluntary severance terms) causing an exodus of expertise from the agency. Finally, there has been a schism between President Trump and Elon Musk, CEO and founder of SpaceX which may affect future exploration policies. Consequently, the first lunar landing attempt of Artemis III, planned for 2027, looks likely to be delayed further.

Thankfully, the space launch system (SLS) has survived attempts to prematurely curtail it. Instead, it will run until at least the fifth Artemis flight, meaning that there will be more than one landing attempt. Nevertheless, the plan to get the SLS translunar injection (TLI) payload uprated to above 42 metric tons, using the exploration upper stage (EUS), is under threat. With a proposed career of only three more flights, the EUS development does not represent value for money and some have suggested that a cheaper design should be considered.

Another piece of happier news for NASA was that engineers finally found solutions to a fault with the Orion space capsule’s Avcoat ablative thermal protection system. These include a change to the re-entry profile, designed to reduce the bubble-inducing ‘dwell time’ skip. Orion itself has strong support, and Lockheed Martin is even considering making it available commercially.

Another example of progress being made is the production of a new lunar surface space suit by Axiom.

With respect to the landing system, some have openly questioned whether converting Starship into the HLS was the right choice. Its height – it is taller than the Statue of Liberty – coupled with a relatively high centre of gravity, makes it more prone to tipping over in the lunar environment. Even with its anti-topple thrusters this is likely to be a headache for designers. Meanwhile, the Starship HLS cryogenic technology is still immature, and its testing programme is intertwined with the delayed Starship launch schedule.

For these reasons, former NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine criticised the choice of the derivative of the SpaceX Starship for the Artemis human landing system at a Senate hearing. With its complex multiple refuelling requirement and technology delays, he suggested that it would be the main reason why China was likely to beat the US back to the Moon.

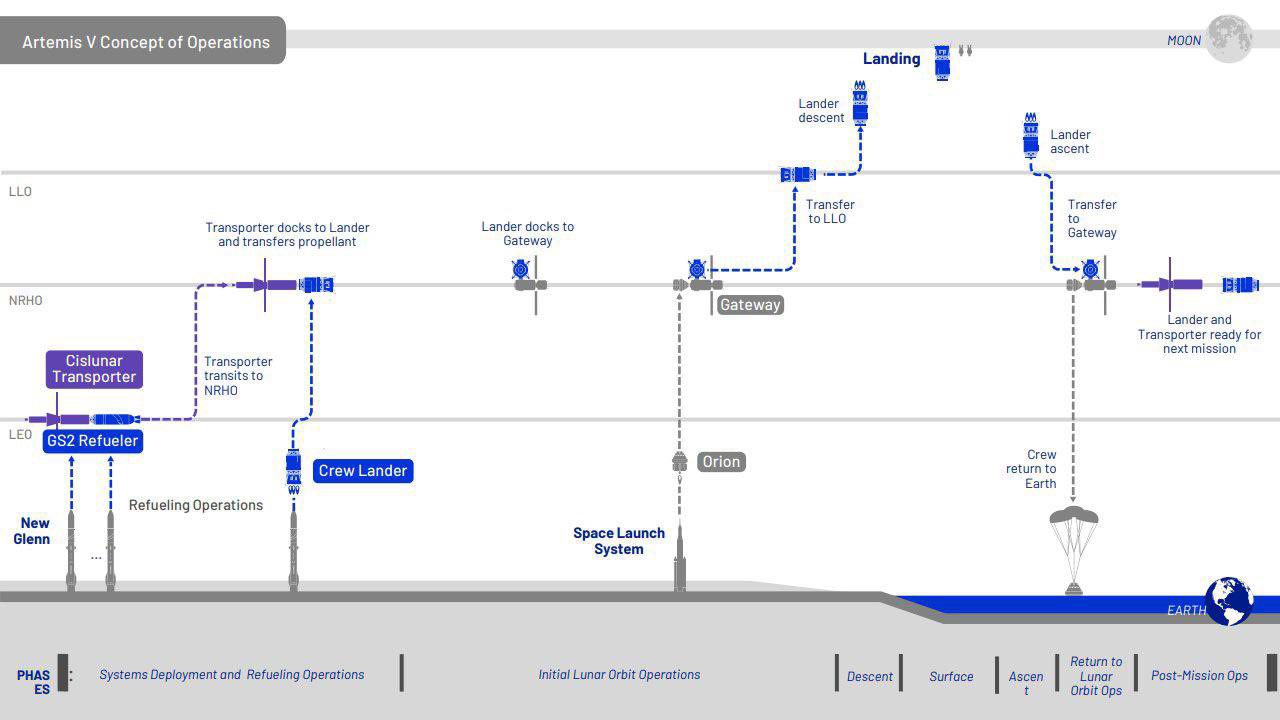

Nevertheless, while the prospect of a US return to the Moon is receding into the distance, there is hope. It is probably too late to start on a simpler storable propellant lander like the one that China is apparently using. However, Blue Origin’s own cryogenic HLS, dubbed Blue Moon, is waiting in the wings. While it originally lost out to SpaceX for the first two Artemis landing missions (III and IV), this design was subsequently selected by NASA as a follow-on lunar lander for Artemis V. In many ways, this lander, whose unmanned versions are about to start flying, is a better design. It is much shorter and thus less prone to toppling over in the 1/6 g environment of the Moon. The Blue Moon lander also probably requires at least eight fewer cryogenic refuelling operations than the SpaceX Starship HLS.

SpaceX Starship-based Human Landing System (HLS) for NASA. Courtesy: NASA

With SLS operations extended until at least Artemis V, and with a Blue Origin landing system fully operational, at least three lunar landing attempts can take place. Thus, the US might just be able to beat China to the Moon if it acts swiftly.

Blue Moon refuelling and landing plan. This version uses the Lunar Gateway, but it is not really needed. Courtesy: Blue Origin

For Mars, the US retains its leadership. But only because China has no official human landing programme. And because China’s Long March 9 is years behind that of the Starship/Super Heavy combination in terms of development. SpaceX may elect to pursue a Mars landing mission independently from NASA, with an uncrewed flight first, followed by a Starship landing attempt by the end of 2026. What is not yet clear is how SpaceX will be able to restrict boil–off of the cryogenic propellants for the six–month passage. One suspects that any Mars landing system, and especially a return stage to Earth, will need hypergolic (react-on-contact) storable propellants to succeed. SpaceX’s plan for in–situ production from the atmosphere of cryogenic propellants for a return to Earth is still a distant technology.

Artist’s rendition of Starship entry into Mars atmosphere. Courtesy: SpaceX

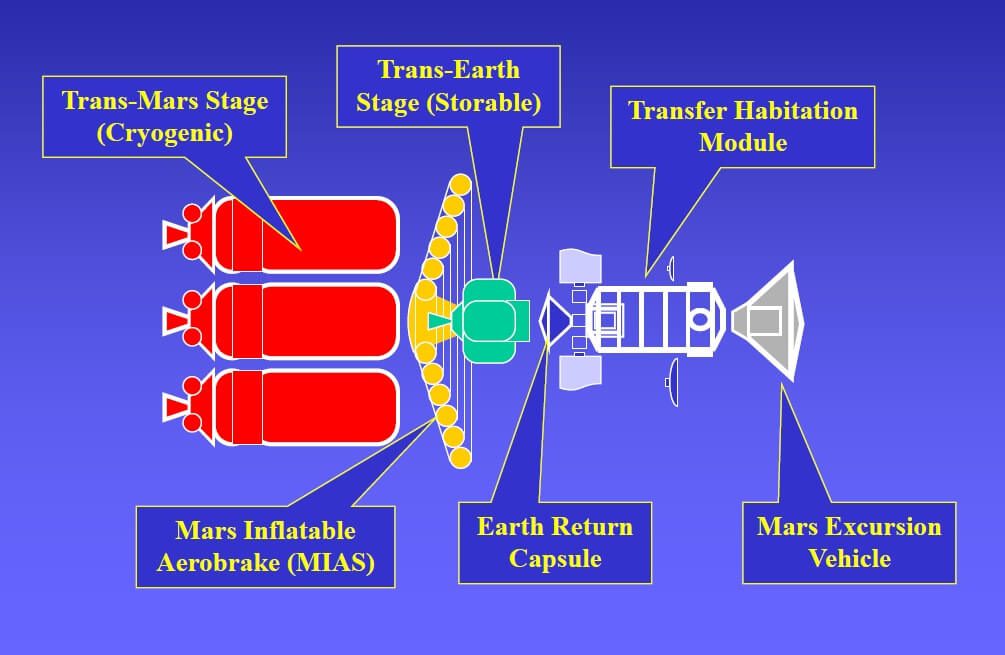

NASA is more likely to select other, more conventional, mission architectures for human flights to Mars. However, Starship’s chemical propulsion may to be used, in some way, for the outbound leg of such missions. This is because Lockheed Martin’s nuclear propulsion research programme, DRACO, has been shut down by DARPA and NASA.

Dr Bob Parkinson’s plan: elements needed for basic human landing mission to Mars. Courtesy: Bob Parkinson/British Interplanetary Society

The combined effect of instability at NASA, the decision to curtail the SLS, and delays to the Starship lunar lander, have pushed out the US odds for a lunar return further, from 5-1 to 6-1. These odds would be higher if Blue Origin was not waiting in the wings. The US maintains its leading position in the Mars race as 1-2 odds-on favourite, but only because China’s Long March 9 is at least five years behind the Starship/Superheavy.

Russia (50-1 for both Moon and Mars)

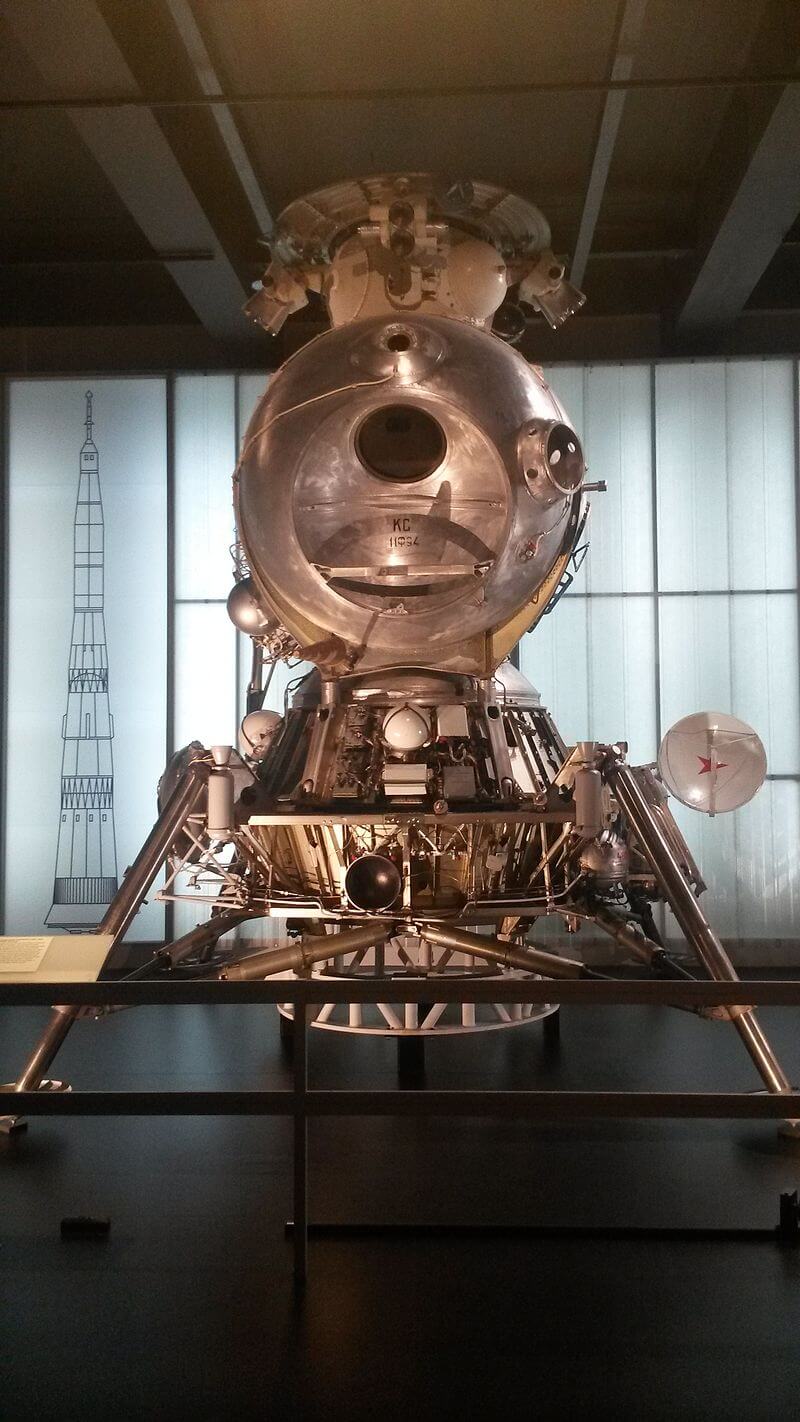

The Soviet Union lost out to the US in the original race to put humans on the Moon during the 1960s. It only managed to send prototype versions of its LK lunar lander into orbit. The chip on Russia’s shoulder could have provided the motivation to outpace its old adversary, but the country shows no signs of recovering its position despite its ambitions.

The Russian LK-3 lunar lander (with a drawing of the N-1 rocket behind it) was only designed to carry one cosmonaut. Courtesy: Wikipedia

Russia officially still has a heavy-lift launch vehicle in development. The Yenisei/Don is a 140 metric ton payload-class rocket. It consists of:

- six booster ‘first’ stages, each powered by two LOx/kerosene RD-171MV engines;

- a central single RD-181MV core acting as a second stage;

- a third stage employing a single RD-180 engine, again using LOx/kerosene as propellants; and

- a fourth stage with a single LOx/kerosene RD-11D58M engine.

Officially Yenisei/Don is scheduled to make its first flight from Vostochny, Russian Far East, in 2028.

Although some images of Russia’s planned successor to the Soyuz human-carrying spacecraft – the Federatsiya – have been released, the programme’s progress is unknown. Similarly, little has been said about the development of a Russian human lunar.

The main problems facing Russia is a lack of funding due to the war in Ukraine and the fact that much of its space expertise has retired, or ‘expired’. As such, Seradata cannot see Russia being ready in a position to launch a human lunar mission before 2040.

Russia’s Lunar and Mars race odds have stayed at 50-1 for both.

India (33-1 Moon, 200-1 Mars)

India’s first attempt at human spaceflight on its own spacecraft (Shubhanshu Shukla recently flew to the ISS, but on a SpaceX Crew Dragon) is expected in 2026, two years later than originally envisaged. Three test launches will take place before that (including one with a dummy Gaganyaan (Indian astronaut) aboard to ensure that everything works. Although the agency has formalised its intention to land its astronauts on the Moon, it does not seem to be in a rush. ISRO wants to achieve the feat before 2040. As we noted last year, the nation should not be underestimated should the others stumble. It proved its lunar prowess with the Chandrayaan-3 mission in August, which saw a lander and rover touch down on the far side of the Moon. Chandrayaan-4, a lunar sample return mission, is already in the works.

India’s lunar ambitions were on display at the IAC. Courtesy: Farah Ghouri

India showed off its plans for a human lunar mission at the IAC in Milan. Courtesy: Slingshot Aerospace/Farah Ghouri

India also intends to launch its own multi-module space station, named Bharatiya Antariksha Station (Indian Space Station), into LEO in 2035.

This relatively new spacefaring nation has already demonstrated that its spacecraft can reach Mars with its Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), or Mangalyaan. As such, while its odds have dropped to 33-1 (from 50-1) for the Moon, setting it ahead of Russia, its odds for the much more ambitious Mars mission stay at 200-1.

New Entrant: South Korea is 100-1 for Moon, 500-1 for Mars, while other nations remain at 1000-1 for both

Moon is a famously common surname in South Korea. By nominative determinism, you could say that its destination has been set.

The Republic of Korea (South Korea) has officially announced its intention to build a lunar base on the surface of the Moon by 2045. The country’s space agency, Korea AeroSpace Administration (KASA), wants to make a robotic landing on the Moon – in 2032. It also plans to fly a, presumably human capable, logistics lander, in 2040.

Although the intent is clear, we at Seradata will have to see more actual hardware before we can give South Korea odds of less than a 100-1 for the Moon, and 500-1 for Mars.

While Japan and Europe are content to take a back-seat ride with NASA to the Moon, some surprising contenders have cropped up from other corners of the world. For example, Iran has expressed its desire to attempt a human lunar landing. Given that this is highly unlikely anytime soon, Iran remains a 1000-1 outsider for both the Moon, and Mars.

China is ahead but all is not lost for the US

The Moon offers significant commercial and scientific opportunities, ranging from astronomy and space tourism to raw materials through mining. No wonder that spacefaring nations are battling to reach it. For its initial lunar landings China has, in our opinion wisely, taken a much more conservative approach that involves repurposing its large rocket technology. Even its lunar lander is conservative and is thought to use simpler storable non-cryogenic propellants.

The US could still beat China, but only if clearly defines its launch and lander strategies and maintains the SLS for several landing attempts.

‘China Manned Space Flight Office’ will be in a position to attempt a human lunar landing by 2028. If successful, it will become the first nation to return humans to the Moon, effectively making it the world leader in human space exploration. With respect to Mars, we can expect a human Mars landing towards the end of the 2030s. That still will probably be a US-led mission, but the underpinning technology and company are, as of yet, unclear.