On 31 October, a Long March IIF launched from the Jiuquan launch site in western China. The successful launch carried a Shenzhou 8 capsule, which, though capable of carrying taikonauts, was empty.

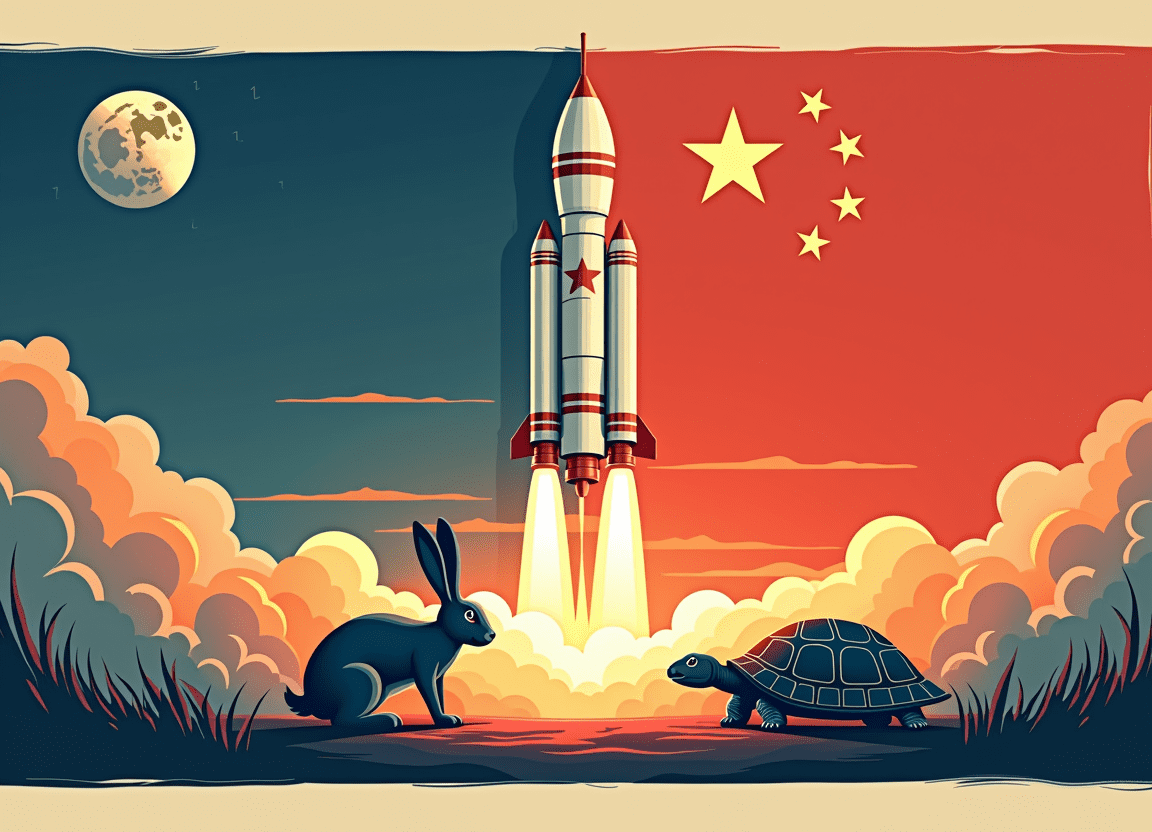

On 2 November the capsule docked with Tiangong 1, a space station test bed, making China only the third nation to bring two spacecraft together in orbit (excluding international collaborations like Apollo-Soyuz and ISS).

Despite outwards congratulations from the US government, the general reaction to China’s spacefaring has largely been one of suspicion (and occasionally outright hostility). Not that the US government as a whole is afraid of China, but there is enough to drive policy towards exclusion.

Take as an example the recent Congressional hearing, in which Rep. Frank Wolf (R-VA), to name one, is vociferous in denouncing any collaboration with China, despite that such collaboration is already legally banned. The result is that NASA is barred from sharing innocuous data with the Chinese government, or even meeting with Chinese representatives. Another result is that China is banned from docking with the ISS — possibly not a deciding factor but certainly an influence on the Chinese decision to build a competing space station, which should be finished by 2020, the year that ISS is due to deorbit.

Bob Bigelow, speaking at ISPCS in Las Cruces, gave a controversial talk in which he posited that China is preparing to lay claim to much of the moon and Mars. His solution is to get there and lay claim first.

One might be reminded of the Red Scare from the Cold War, when any Soviet move was an escalation, and so was any potentially adverse move by anyone else, for that matter. The US reaction resulted in both positive (landing on the moon, rapid technical development) and negative (nuclear bombers on alert, several wars); in any case, in retrospect it often turned out to be a serious overreaction, and sometimes provocation. The Soviets did this as well, believing they were under essentially the same threat we believed ourselves to be under.

There are opportunities for collaboration, for trust-building measures that the US is wilfully ignoring. Competition can be a great thing, but too much competition and the results play out in other areas. In scientific and economic realms, US institutions are busy forging bonds in China that affect the policy of both governments. Space can be a unique, mutually beneficial stage for collaboration or geopolitical trust-building measures; instead it is currently a measure of distrust and fear. China is not an enemy on the scale of the Soviet Union, nor really even a peer competitor. It is puzzling that so many people seem to believe otherwise.