The mysterious disappearance of the Malaysian Airlines Boeing 777-200ER jet airliner (on Flight MH370) with 239 passengers and crew in March has resulted in Earth observation spacecraft of various nations being tasked with finding the location of the presumed crashed aircraft and its “black box” flight data and voice recorders. Meantime, along with recent radar plots, recent satellite images and early warning records from the region are currently being examined for any clues as to the aircraft’s location. The main identification and tracking transponder on the aircraft was apparently not working at the time of is disappearance.

Claims that Chinese satellite images had identified three large items of suspected debris in the South China Sea have now been discounted. Subsequent satellite imagery (by the WorldView 2 satellite) detected a debris field in the ocean South West of Australia. The debris field is now being investigated by Royal Australian Air Force ocean reconnaissance aircraft.

The initial clue that the aircraft might have been heading south in the Indian Ocean came from the London-based satellite communications firm, Inmarsat, after it revealed that it had been receiving a “handshake” hourly test signal from carrier wave of the Malaysian Airlines aircraft for seven hours after its last voice contact with air traffic control. While this signal test carried no data to directly give a position of the aircraft, engineers are used this signal data (its transmit/receive time delay and signal strength attenuation) to work out an approximate direction from whence it came. As it was, before the aircraft went out of tracking range, military radars in the area apparently were able to record the aircraft going off in an unplanned direction towards the Indian Ocean.

Total power failure remains a possible cause/effect of the suspected disaster as not only was normal contact ended with the aircraft, the automated ACARS aircraft systems’ monitoring transmissions from Flight MH370 had also ended mysteriously. While the main communications systems might have been knocked out in this way, a power failure might also have seriously affected the airliner’s navigation systems which, in turn, could have resulted in the aircraft flying off course. Other experts have that an unexpected depressurisation or fire might have caused this power failure and, at the same time, either disabled the flight crew or disorientated them enough to take up a new emergency heading, or forced them to do so, before they lost consciousness.

Most mysterious of all is why the Boeing 777’s own conventional transponder, which ground stations could have picked up before the jet went out of range, was apparently not working even though it should have had its own independent protected power supply (usually a battery). Then again it may have just been switched off (possibly by a disorientated crew) or had itself succumbed to fire itself. Either way, for the time being investigators note that they still cannot rule out this event being a 9/11 style act of terrorism or a hijacking attempt, or even a pilot’s suicide attempt, with suggestions that the main tracked systems on the aircraft: the transponder and the ACARS system were deliberately switched off. Even if this had been done, the actual carrier wave that was sometimes used to carry ACARS data via Inmarsat’s satellites, remained in operation.

While satellites helped this time, to avoid such mysterious aircraft disappearances in future, air traffic authorities around the world are now investing in the ADS-B system. The satellite aided ADS-B (Automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast) system will be able to track the position and height of all major aircraft in real time as derived from GPS or Galileo (or equivalent) satellite navigation data even over remote deserts and ocean areas.

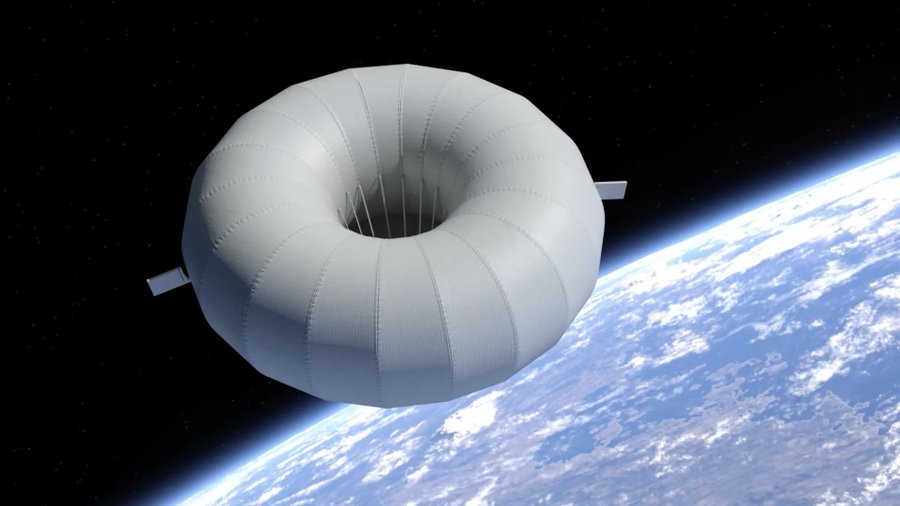

While ground stations will still be the primary receivers of this information, ADS-B tracking receiver payloads will also be carried by new generation Iridium NEXT spacecraft which will allow aircraft’s position to be continuously relayed via inter-satellite links from regions where normal radars and ground stations cannot reach. In February, Iridium’s joint venture with Nav Canada, Aireon LLC, has recently signed a 12 year agreement with the NATS, the United Kingdom’s privatized provider of air traffic control services to share ADS-B tracking data for aircraft over the North Atlantic.

Had it been carried, ADS-B, should thus have been able to track the missing Malaysian Airlines jet even in the middle of the Indian Ocean where radar coverage is limited to any naval vessels present. In this latest missing aircraft mystery, the signals received by Inmarsat appear to indicate that the aircraft was airworthy for at least five hours after the last crew voice transmission. It is now thought that the aircraft had carried on flying into the Indian Ocean until its fuel ran out or until it landed. Some media reports suggest that the final “handshake” test signal to Inmarsat satellites seven hours after the last crew radio transmission must have made been after the aircraft had landed given the amount of fuel aboard.

It has to be noted that while ADS-B promises an end to most missing aircraft mysteries in the future, the ADS-B transmitter, independently powered or not, still has to be switched on for it to work correctly.